On the Unfortunate Cosification of Crime

Strap in, kids, we're getting critical.

When I was about eight or nine, I experienced that near-universal nerdy small child rite of passage: an obsession with Greek mythology.

I know, that is not a sentence about crime. We’ll get there; just hang on a sec.

I loved me some Greek myths, is what I’m saying. I had illustrated guides. I had books on tape. I had the Horrible Histories book with the Trojan horse joke on the cover. It was A Phase.

And a couple of short years later, it was followed by a much more lasting one: crime fiction. (See, there you go).

Unfortunately for the general narrative of this substack, I don’t remember the first Agatha Christie I ever read. But I can tell you that I went on to read almost all of them*. A quick run-through of favourites for you: her best detective is Poirot. The best Poirot novel is Five Little Pigs. The best adaptations are the ITV Agatha Christie’s Poirot series – I once literally cried at the idea that I might get to meet Hugh Fraser, who plays Captain Arthur Hastings** – with an honourable mention specifically to the ’70s Peter Ustinov version of Death on the Nile. Find me a film with a better cast and better costumes. YOU CAN’T.

*All the Poirots and all the Marples; I can take or leave Tommy & Tuppence, because I’m normal.

**I am fine.

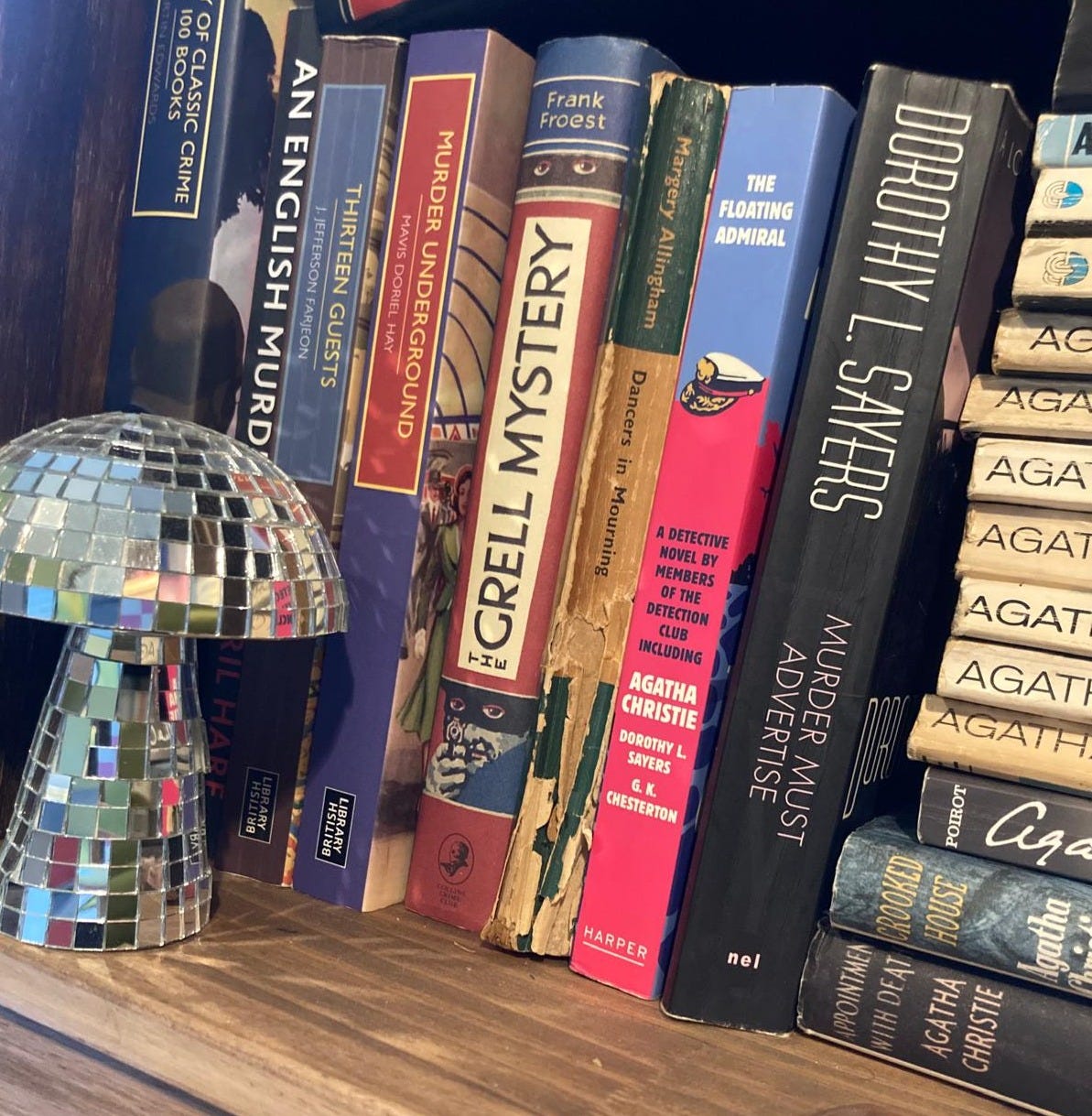

From there it was Arthur Conan Doyle and Sherlock Holmes; Dorothy L Sayers and Lord Peter Wimsey. Patricia Highsmith’s incredibly written and even more incredibly nicknamed series The Ripliad. Even a touch more modern with PD James and Ruth Rendell. And I’m not not there still.

I’m not alone in any of this: Crime is one of those genres that’s always, always popular.

It’s familiar – generally speaking, you know a mysterious thing is going to happen, you know you’ll get clues and red herrings and suspects, and you know at the end you’ll find out how it was done. Even the subversions of the genre are ultimately singing off this same hymn sheet, just a little off-key.

But it’s also unfamiliar, every time: you don’t know what is going to happen and you don’t yet know how it was done, and even if you think you’re working it out. So the end result is a sort of plus ça change situation – haven’t you ever wished you could reread a favourite book and have your first experience of it over again? With classically formatted crime, you basically can.

And crime is gossip. It’s a friend saying, “You’ll never believe what happened,” or “Oh my god, did you hear?” or even, in some cases, the delicious “Can I be a bitch for a second?” Everyone loves a story with a twist.

Like gossip, though, true crime comes with a caveat. It’s the responsibility of making sure that the content you’re consuming isn’t exploiting or trivialising the actual experiences of real victims and/or their families. I used to listen to murder podcasts, but I got put off them because a) that is the medium I’ve found most guilty of blurring those ethical boundaries; and b) there really is only so much time one can spend listening to stories of real, awful things that have happened to people, usually to women, committed by men.

Documentaries are a bit safer – as I write this my boyfriend Chris and I are two episodes into Death Cap, the one about that woman in Australia who murdered her lunch guests with mushrooms. Extra fascinating to me is The Staircase, about a man on trial for the murder of his wife, because the accused was extremely involved in the production of the documentary and still, somehow, doesn’t come across as that good a guy. It just always bears thinking about – are they being respectful about it? The answer is often no.

So fictional stories are generally a better bet, morally speaking. I am absolutely addicted to the BBC’s terrible-but-also-sublime Death in Paradise. The BBC is home to a rich seam of good ol’fashioned crime TV, actually: there’s the charmingly meta Magpie Murders. Every episode ever made of Jonathan Creek, although probably don’t bother with the later specials. It’s Maddie Magellan or bust.

Many of you have probably already seen the new Knives Out, with mouse-turned-human Josh O’Connor, and like me are gearing up to watch it again with your family at Christmas, with added pauses to explain the plot to relatives. (Personally: the performances are pretty good and it’s still silly and fun, but the solution left something to be desired.) And, obviously – remember what substack you’re reading – there are still books.

Christie, Dorothy L Sayers, GK Chesterton and their ilk, as a collective, are often referred to as The Golden Age of Crime, and honestly, there’s enough there to keep you going for years. There is a reliability of quality there, which can be a bit harder to dig out from the flood of titles from more recent years.

A few years back the big boom in crime fiction was in what we could call the category of Sort of Neurotic Woman Is Right All Along. You know the ones: something’s going on! She’s the only person who can see the truth! Everyone thinks she’s crazy! All the titles have girl or woman or lost or dark in them. There’s Before I Go to Sleep. Girl on the Train. Woman in Cabin 10. Whatever that one is called about the psychologist with agoraphobia. Some of the books in this category are really good. The rest of them are something that is not that.

And then there’s Richard Osman. Among others! I don’t mean to pick on him! But unfortunately I semi-recently watched the worse film made of his bad novel, so here we are.

Look. To anyone who enjoys these books, you don’t have to listen to me! Even though I am extremely cool, I am not actually the arbiter of taste, and my feelings on this matter are not fact.

Those feelings are, in short, that those books are not very good. Or, more specifically, that they are a less good version of a good thing. Like those later episodes of Jonathan Creek, they’ve taken the cosiness a little too far, and the upshot is that it feels dumbed down. This type of crime fiction is supposed to be easy to read, but not boring.

It’s plenty cosy enough to set your mystery in a retirement village and to have some pensioners as your investigators – Christie managed it with Marple; every secondary character in those books spends several paragraphs thinking about how old she is, and how frail she looks, and how very white her hair and how unimaginable it is that a woman of such very advanced age could think about anything besides, I don’t know, knitting. (Marple does love knitting. She contains multitudes.)

And Osman has directly invited this comparison by taking title inspo from a Marple short story collection: The Tuesday Night Club, in which various characters tell stories of mysterious crimes/goings on they have witnessed, and (extremely obvious spoiler alert) Miss Marple pipes up with the solution every time. “We hardly knew the old woman was playing,” says one incredulously.

Shoehorning in modern or “thrilling” elements to the TMC series – property development! Cartels! Diamonds! – doesn’t take away from the unending tweeness of it all. And, in fact, feels like a jarring choice for the style of novel Osman is ostensibly trying to emulate. He’s smashed that style together with those thriller tropes and, for some reason, a reading age that is about a decade too young for his target demographic. Much of the first-person narrative is cluttered with “by the way” and “anyway” and “you know?”, like he was trying to pad out the word count of his essay. There’s just nothing worse than a bad example of a great thing.

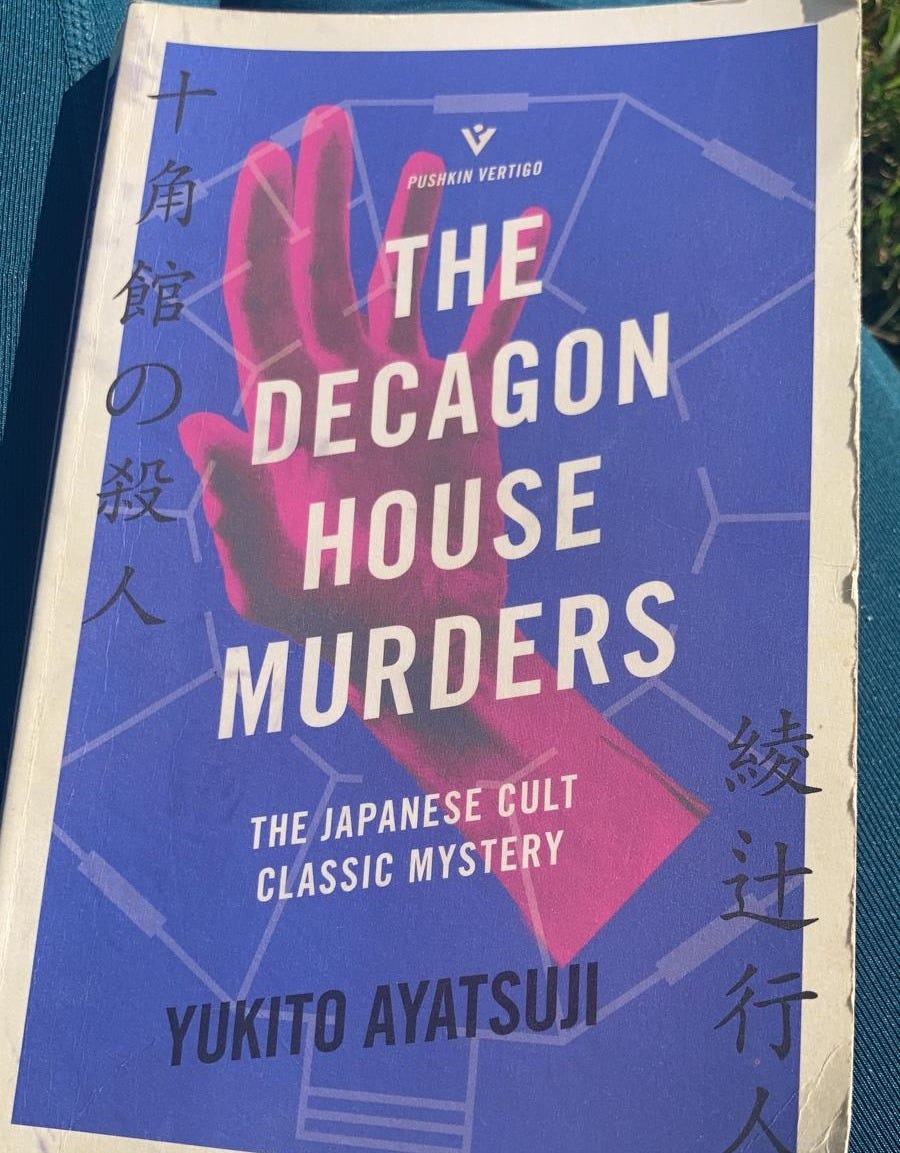

For me, it’s all thrown into sharp relief by the fact that it is possible to have a well-worked modern iteration of those classics. There’s some great stuff out there! Japanese crime writer Yukito Ayatsuji’s fantastically named Bizarre House Murders each takes place in, shocker, a weird building, usually in the form of a locked-room mystery. Start at the beginning with 1987’s The Decagon House Murders – there’s still time to pick one up to sneak away and read by the fire next week when your uncle insists on watching a Harry Potter film (vom).

Less adhered to the classic template are stunners like Tana French’s Dublin Murder Squad series – each one focuses on a different detective in the same department, so you’ll find the office villain of one book as the hero of the next, and the twisty, complicated cases are intertwined with their personal lives. Yes, that’s right: it’s The Detective Whose Personal and Professional Lives Blur Together! But some of the best work in that category I can think of: they are genuinely all very good, but my favourites are The Likeness (doppelgangers!) and The Secret Place (complicated teenage friendships!).

Rebecca Makkai surprised me in 2023 with a taut, grippy crime novel, I Have Some Questions For You – its predecessor, The Great Believers, is brilliant too, but there’s not a wisp of murder in it. We love a versatile queen. IHSQFY is also a campus novel, and also also tackles the crime podcast/Youtube industrial complex, so it’s just fat with treats.

On my list of books to read before the end of the year is Darkrooms by my pal Rebecca Hannigan, out in Jan, which I haven’t started yet but is giving me some distinct Tana Frenchian vibes. And – ’tis the season – a lot of my old Christie collection is still living at my mum’s, so some of my favourites are absolutely ripe for a festive reread.

All the books above are hopefully available in your local bookshop, or there’s always UK Bookshop, Abe Books or World of Books online.

Pop over to BBC iPlayer for, honestly, most of the cosy crime TV you could ever want.

My current read is Give Me Everything You’ve Got, by Imogen Crimp. No murder yet, but there’s still time.

Incredible pay-off in this for me, personally, above and beyond the excellent commentary, omg!

Your take on the "cosification" of crime fiction really resonates with me. The distinction between cosy and dumbed-down is so spot-on because there's a craftsmanship in those Golden Age mysteries that modern imitators often miss. I remeber reading my first Dorothy L Sayers novel in college and being struck by how intellectually engaging it was despite being "light" entertainment. The puzzle respects the reader's intelligence rather than spoon-feeding everything. When I was traveling through England a few years back, I picked up a bunch of used Christies from bookshops and spent rainy afternoons solving murders, and it never felt patronising like some contemporary cozy mysteries do. That balance of accessibility and genuine cleverness is really tough to replicate.